Renaissance through sustainability

The Marsala from the town on the west coast was the Sicilian wine which was best known internationally for several decades. Produced in very large quantities, this fortified wine was initially competition for sherry. At the end of the 20th century the market was then flooded with ever increasing volumes of the wine which was being produced at ever cheaper prices: In the finish the wines were being stretched with egg yoke as a sort of premixed flip. The few quality producers, who produce a quality version of this wine today, fill a niche with it in addition to the well-known sweet wines such as Moscato di Noto or Malvasia di Lipari.

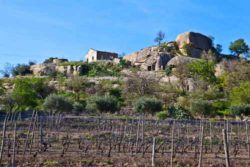

It was only in the late nineteen-eighties that Sicilian wines stepped onto the international stage. Ironically as an alternative to Australian wines, due to the fact that it has a similar climate. Customers wanted dry wines as it was, and they found them just a little inland along the west coast. Right there where Tomasi di Lampedusa’s historical drama “Il Gattopardo” is set, a story about change being forced upon the people during the period in which the Italian state was born, 85 percent of Sicilian wines continue to be produced there a good century later. It was in this maritime climate that the first Chardonnays which could hold their own internationally were produced. The wines such as Planeta’s “Cometa” were even more important. A wine with dense mineral characteristics was developed from the original Campanian grape Fiano, a wine which pointed the way with respect to the renaissance of Sicilian wine cultivation.

The style of cultivation aims, in particular, to be sustainable and authentic, with 25,000 hectares or 38 percent of the wine gardens being cultivated organically. “And we are not doing any ‘green-washing’ here, that is something that the world needs to know,” says a proud Francesco Ferreri, owner of Valle dell’Acate and President of Assovini. The merger of quality-orientated vineyards, both big and small, places a great deal of importance on giving each member the exact same voting rights. The average age of the board of directors is 40, and the ratio of women is consciously very high. This is meant to underline the fact that this is not an old-men’s club that stands in the way of change. Founded in 1998 by the three fathers of the Sicilian wine renaissance Planeta, Donnafugata and Tasca d’Almerita, the 72 members today represent 80 percent of all wines bottled. The main goal is to be successful on the foreign markets and that as a quality wine.

Autochthonous vines have a main role to play in this pursuit. “We have after all over 60 different types of vines,” explains Antonio Rallo, President of the Wine Makers Association, “and there are new types being included all the time.” Almost every third Assovini winemaker cultivates test plants, from which high-quality vines are selected. In the course of cultivating these vines, names like Vitarolo, a type of white wine, came to light, for which “only a single vine remained in existence in the garden of a ninety year old,” explains Rallo. The University of Catania even hopes to find out how the Romans cultivated grapes for wine production by carrying an experimental test planting.